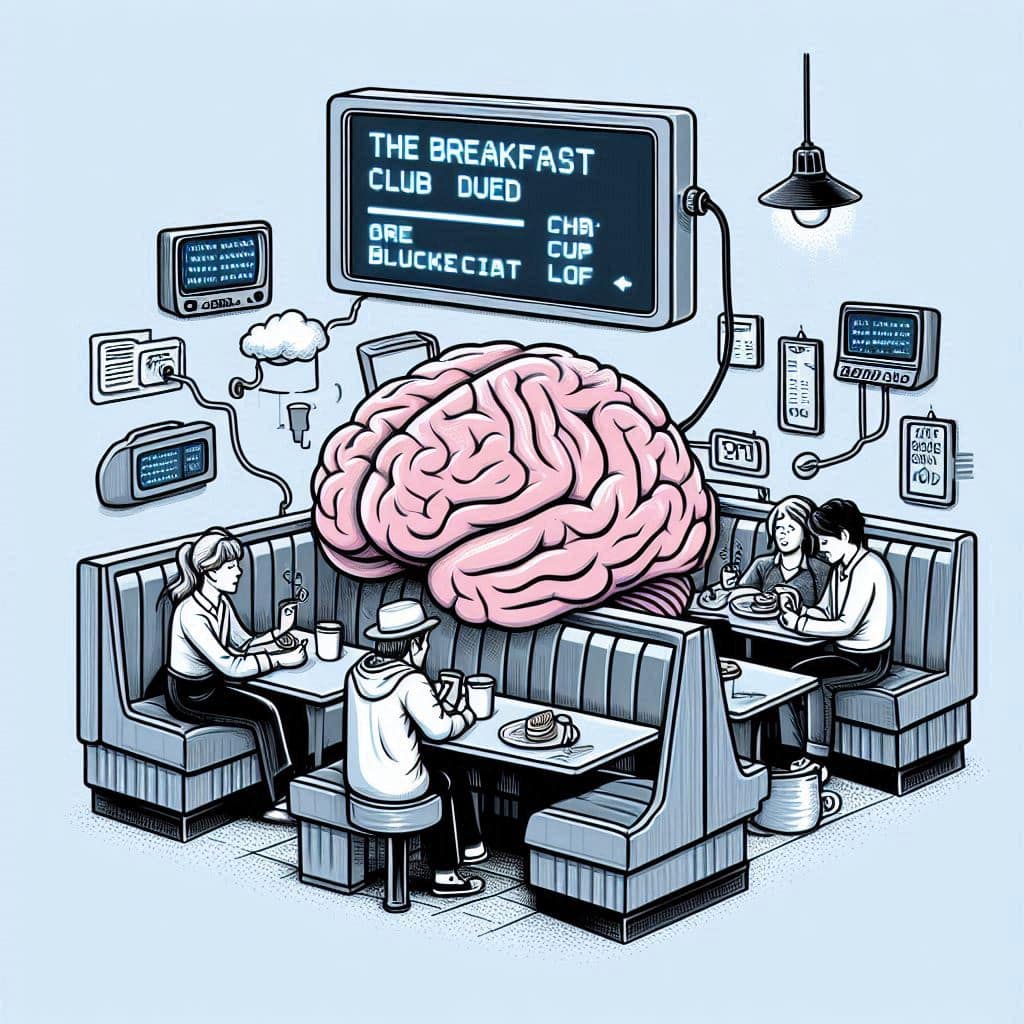

How John Hughes Used an Analog Second Brain to Build a Writing Life

John Hughes, legendary director of The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and Sixteen Candles, didn’t just write films — he lived a writer’s life. When he passed away on August 6, 2009, just days after my 29th birthday, I was in grad school for writing, but I hadn’t yet figured out what it truly meant to live as a writer.

That changed when I read David Kamp’s profile of Hughes in the March 2010 issue of Vanity Fair. For the first time, I saw what a fully engaged creative life looked like. Hughes processed the world through pocket notebooks — mostly Moleskines and sometimes even high-end Smythson ones. Long before digital second brains were a trend, Hughes used pen and paper to make sense of life.

His notebooks weren’t limited to polished ideas. They were filled with quick sketches, overheard dialogue, emotional reflections, and raw thoughts. He didn’t wait for inspiration; he created a lifelong habit of documentation. This analog method acted as his “second brain,” a reliable archive of ideas he could return to whenever needed.

Interestingly, Hughes first dreamed of becoming a painter, and this visual sensitivity carried into his writing. His films felt painted in words — rich with emotion, framed like art, and grounded in the honest chaos of adolescence. Kamp captured this beautifully: “John Hughes never stopped writing… Writing was Hughes’s way of making sense of the world.”

That quote changed everything for me. It helped me understand that a “writing life” is not about waiting for perfect sentences. It’s about noticing, recording, and building a practice of reflection. It’s about carrying a notebook, like Hughes did, to jot down a moment before it disappears.

Inspired by his method, I started keeping my own notebook. At first, it felt unnatural — scribbling partial thoughts or scenes without context. But over time, it became a natural extension of how I experienced the world. Like Hughes, I began seeing potential stories in the ordinary: a passing glance, a turn of phrase, or the way someone laughed.

This analog second brain became not just a creative tool but a way to stay present. It made me slow down, pay attention, and reflect. Hughes’s method reminded me that some of the most profound stories don’t come from waiting for a muse — they come from daily observation and honest documentation.

In today’s fast-paced, tech-saturated world, Hughes’s analog approach feels radical and grounding. His notebooks weren’t just tools — they were lifelines, sanctuaries for ideas, and proof that writing starts long before you open your laptop.

Over a decade later, I still carry a notebook, and with it, a little bit of John Hughes’s spirit. His commitment to capturing life as it happened taught me that writing isn’t about chasing perfection — it’s about paying attention and giving your thoughts a place to live.